Vishwajit Nimgaonkar, lead investigator, said, “Our study is one of the few to assess viral exposure and cognitive functioning measures over a period of time in a group of older adults. It’s possible that these viruses, which can linger in the body long after acute infection, are triggering some neurotoxic effects.”

The researchers examined blood samples to uncover traces of viral infections in over 1,000 people over the age of 65 who were also evaluated for cognitive change over the course of five years.

CMV, HSV-2, or toxoplasma exposure was found to be associated with different aspects of cognitive decline and could relay itself as a possible explanation for age-related cognitive decline.

Senior investigator Mary Ganguli added, “This is important from a public health perspective, as these infections are very common, and several options for prevention and treatment are available. As we learn more about the role that infectious agents play in the brain, we might develop new prevention strategies for cognitive impairment.”

The researchers are now looking to uncover the specific areas in the brain that can become affected by viral infections.

Viral infections leave marks on immune system using gene signatures

Stanford University School of Medicine researchers have found that distinctive gene expressions are what distinguishes people with bacterial infections from those with viral infections. A second finding of gene expressions can also differentiate between those with the flu and those with respiratory infections.

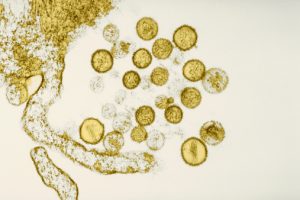

When a virus or bacteria enters the body, it sets off a chain reaction in the immune system, changing the expression of hundreds of genes.

Lead researcher Purvesh Khatri, along with his colleagues, identified 396 human genes, whose expressions changed in specific patterns to reveal a viral infection. This pattern occurs in many viruses and differs in those who are healthy and those who have bacterial infections.

The study also outlined a second string of expressions that help identify the flu, which consists of 11 gene expressions.

Khatri said, “It seems that when there is a viral infection, the immune system turns on a general response to all viruses, followed by a virus-specific response to the particular virus. You can imagine a decision tree where the immune system asks, ‘Is it bacterial or viral?’ And if it’s viral, it turns on the meta-virus signature response. And then it asks, ‘If it’s viral, which virus is it?’ And then it turns on a specialized response for that virus.”

The findings help further the research team’s goal of being able to correctly identify illness in healthy individuals and then prevent or treat it.

The researchers are also working towards determining the effectiveness of vaccines and whether or not individuals are responding to them. “The goal of vaccination is to generate the same immune response without the symptoms. If the IMS response is truly virus-specific, we should see the same response in vaccination,” added Khatri.

The researchers found that the key 11 gene expressions were not present in those individuals in whom the vaccine did not work, meaning the individuals were not responding to the vaccine.

The researchers will continue their studies in order to uncover more about vaccine effectiveness to better understand how to make it more universally effective.